About fashion, design and African cultures

In conversation with the fashion artist Bubu Ogisi

When Bubu Ogisi got out of the car, she said: “I will have to leave in 30 minutes!”. I guess we made our disappointment quite visible as she added almost immediately: “I should be able to change my train ticket, though”. Indeed, we spent hours together, at the Cité du Design, talking about fashion, textiles, Africans cultures... After wandering around the Biennale exhibitions with the mediator Tina, student at Ensadse, we launched the discussion, and had lunch.

The story behind your name, Bubu Ogisi, is a very nice one…

I was born in Nigeria. My first name is very long, it has 13 letters! When I was a baby, my sister used to call me Bubu, for me to stop crying (laugh). Then I went to school in foreign countries, in Ghana, in France… There, people couldn’t pronounce my Nigerian name. I told them: « just call me bubu ». That's how my name became Bubu, to make it short!

How would you define yourself in your work?

I am a Creative Director, a fiber artist and an experimental researcher. My work is rooted in my origins and my lifestyle. My creativity derives from the way I grew up and lived. In my work, I intend to move and have impact for other people: this is how design works, and aesthetics evolve through emotions and experiences.

You studied fashion at Esmod Paris: what is your relationship with France?

I chose to study in France because I wanted to be in contact with the French-speaking way of understanding - as I was really used to the English-speaking way of understanding until then. It was crucial for me to learn another language and to experience how the language affects the people and the way they design, eat, create, and live! Language is a crucial foundation in my work as different languages have different conceptual approaches to existence.

You seem to have a special relationship to languages: what are languages you speak?

As I went to school In Ghana, I speak the Twi language. My mother’s tongue is Itsekiri. I also speak Yoruba.

When did you start making clothes?

Oh well… I started a long time ago (laugh). When I was a child, my mum usually gave out fabrics as presents/gifts quite often. I preferred the fabrics to shopping at the ready-to-wear shops because I always thought no one understood my style or what I wanted to wear. Very early, I knew what I wanted to wear and what I didn’t want! I used to tell my mother: “Give me the fabric and I would go to the tailors and I would tell them what I wanted and draw to show them how I wanted the outfit put together.” If my outfit wasn’t ready, I simply didn’t go out (laugh). As I was very shy, I considered that my clothing was speaking for me. As a child, I enjoyed using my outfit as a vehicle of communication. I became obsessed with clothes! You can learn so much about somebody from what they wear…

What do you like in fabrics?

I love the idea of how fabrics are seen as protection. I love natural fabrics, even if they are damaged : I like to see the way they fall apart. I love their smell too. All the senses are involved in my relationship with natural fibers. It happens with synthetic fabrics also: I love their smell and the sensation to their touch. I guess, this comes from the fact that one can still feel the human impact in man-made pieces even if its seen as a “non-natural manufacture”, therefore the question is : since it is man-made, and man is natural, then does it make synthetic natural?

Who are your clients today?

I work mostly with museums and galleries as well as niche concept spaces in different parts of the world. My pieces are time-intensive so the process of making or fashioning takes a while and only a select few understand this idea of creativity. We strongly believe that this “time” we are invetsing in the making as part of the value of what we create, a ritual meditative pedagogy. If you know that a piece took one thousand days of work, you are not going to throw it away. Thus, there is less and less waste. In addition, it conveys the idea of preservation and archiving pieces that will still exist in a hundred years from now.

Everything I create is to be seen, understood, after I’m gone. It’s always for a later purpose. To me, it would be very selfish if I just created for now, as I am using things from the past, to convey a message in the now for the future.

My research consists of understanding the past, giving room for it in the present, and leaving it for the future.

Today, you have your own brand IAMISIGO, and you are also the Creative Director of Hfactor: could you tell us more about it?

In Nigeria, there were no collectives. With my business partners, we sat down and said « let’s create one ». We wanted to highlight artists from Nigeria but also from outside Nigeria and create a system of exchange. Our goal was to create exchange programs with music artists, DJs, photographers, artists and anyone in the creative field, invite them to Nigeria and work with them here but also outside Nigeria, to reach a larger scale of understanding. A social enterprise engaging with various communities.

We have worked with various foreign organizations within and outside Nigeria, like the Austrian and US consulate in Lagos and Mbassy in Hamburg for example, through our different events and installations, to introduce them to the classless world of creatives. Hfactor is the bridge which brings upper class and lower class together. We are removing the borders of class, bringing all this world together, so everybody can co-exist in a creative way.

You are also the creative director of Vitimbi, a Kenyan fashion brand created by Oliver Asike and Velma Rossa. It is a label with strong political statements engaged in upcycling clothes.

Yes (laugh) I started working with them in 2019. They approached me to come to Kenya and create something very much inspired by Kenyan street wear and street life.

In Vitimbi, everything is inspired by daily life in the streets. In Kenya, everybody has a uniform and a specific color : the tax collector, the taxi driver, the bus driver, the lady who cooks etc. Usually, people don't want to dress like these working people, so we chose these colors and styles as an inspiration, using various upcycled materials. We “fashion” and manipulate the fabrics, mixing them, turning them inside out, matching colors…

All the fabrics come from the infamous recycled market Gikomba, as well as other deadstock fabric markets, involving the spirit of the street into the craftsmanship of every piece. It is a huge highly organized second-hand market! You can stay there all day long, and split into section: jackets, trousers, jeans, tee-shirts… It is a market, open to everyone, very cheap! The core foundation for Vitimbi is to also to engage with the secondhand community. It is about recycling, deconstructing, reconstructing, reusing, and giving it back to the world.

More broadly, my work aims at decolonising minds. I want to remove barriers within my work. Showing how this country is related to this other country, how this place is connected to this one, making connections between everybody and everything.

Does it start with materials?

There are materials you can find here and there, but with a slight difference between this culture and this one. In the way people use them and also in their fabrication: the way they dye them for example. There are also differences in the way they perceive them also. A broom in Uganda will be a decoration in West Africa, and a broom in West Africa will be a decoration in Uganda!

What is the situation of craftsmen and craftswomen you work with?

I am in love with my weavers, they make me so happy! I go to them with a load of new crazy ideas and they are always welcoming them, very excited: « What? You want to mix this plastic with cotton and hemp and dried wood?! Oh my god, we don’t touch this, but we will make it for you. » (laugh) It’s very cute.

I work with communities that are going through an economical reform due to the fact that tapestry making has been an industry that hasn’t seen an evolution until presently or have had their work replaced by machines and the demand for mass production. I work with people who have gone through certain issues and turned to crafting as a form of rehabilitation or reforming. I think it is part of my destiny to positively impact their life and the idea of a future with their craft.

Since you started your brand in 2013, can you see craftsmanship growing?

Yes, 100%, it is becoming a trend now! People are much more interested in craft and tapestry making than before. They see the potential in it, they understand the value of the work and time that has been spent on making things with just our hands.. Weaving takes a lot of time but it is also meditational, you calm down, it’s nice to see small things grow into something huge.

It is also a collective work.

Exactly, it is collaborative: I can’t do everything by myself alone, I’m not a machine. I believe fashion should always be slow, it should never be fast. You need time to understand your style, I had to understand my style, its multiple layers (laugh). When it’s fast, it is too much confusion, too much waste.

What is your relationship with communication tools such as Instagram?

I have a love-hate relationship with Instagram. I hate Instagram! I used to love it ten years ago: it was calm, I used it as a photo editor… Now it’s sooo fake. I choose only to post what I feel is vital. It’s like a machine constantly urging you to feed it. It becomes so demanding and too much sometimes.

I still love Instagram in the way that it brings people visually together and it really helps the visibility for my brand and my work. It also helps people understand our digital energy.

When it was only websites, you couldn’t really understand people's digital energy; whereas on Instagram, you can understand the brands and the people that are behind them. There is always a good and a bad side of everything (laugh).

European consumers start to be conscious that plenty of our clothes are sent to Africa, and that it is causing a problem of waste management. It also creates an unfair competition with local companies, and it is an ethical question. What is your opinion about it?

I see it as a problem but also as a blessing (I always see two sides in everything). It has always existed throughout colonial times. Colonial currency was clothing, colonial masters used old clothings as payment instead of money. So there is a continuum, a neo-colonialism with garments. It is a problem when people see this place as a dumping ground. But the dumping ground reimagines everything, and reuses it… Africans have used it to their own advantage.

But fashion pollutes only slightly less than oil, so we have to focus on how to change this…

In a previous interview1, you said « My work is to free people’s minds »: does fashion free people, you think?

To free people’s minds means helping them to understand the power of the spirit, the power of their own body… I think everybody should be free to create what they want to, to be whoever they want to be, being mindful of how it affects everyone at large. It is a way to play with the norms and question them. Deconstructing, freeing, removing the borders from everything is what I mean.

Could you explain your relationship with spirituality in your work?

First, it is central in the material I work with. For example I work with raffia, jute, sisal, bark cloth and hemp plants as fiber for textile: these are all healing materials. The bark of the trees is used for coronation, funerals, birth and also to preserve the skin. I also work with salt, which has interesting properties and ancient rituals linked to it.

There is a healing, conservative and spiritual element to every material I choose, there is a story behind every piece I make.

We tend to forget about what leads the mind to create but I like how our mind forms a lot of ideas. There is an idea, a spirit, we don’t know where it’s from, we can’t answer all the questions in this world! The spirit has to lead you, there is a need to reconnect... The spirit is absolute, it is unknown, that’s why I like to being incognito and why im obsessed with masks and their multiple personalities.

I currently have an exhibition on that subject, actually. Based on masquerading being the middle ground between the visible and invisible. I see myself as a masquerade maker. It takes a lot of time and certain rituals to create masquerade pieces. You cannot create it in one day.There needs to be time involved, in the fabric, in the process…

The priests, the imam, the high priest, the witch doctor, who are the vessel between the two worlds, have a way to dress, even down to the nails, the powder, everything is well thought. With the body being the ultimate canvas, when we present ourselves to the two worlds, seen or unseen, all of you is a ritual space, your body is a temple. Your body becomes a spiritual landscape, that is the energy field, designed, constantly reworked and reactivited. You design what you wear.. For me, you cannot present yourself to the rest of the world looking “normal”, or you won’t be listened to, you won’t be taken seriously (laugh).

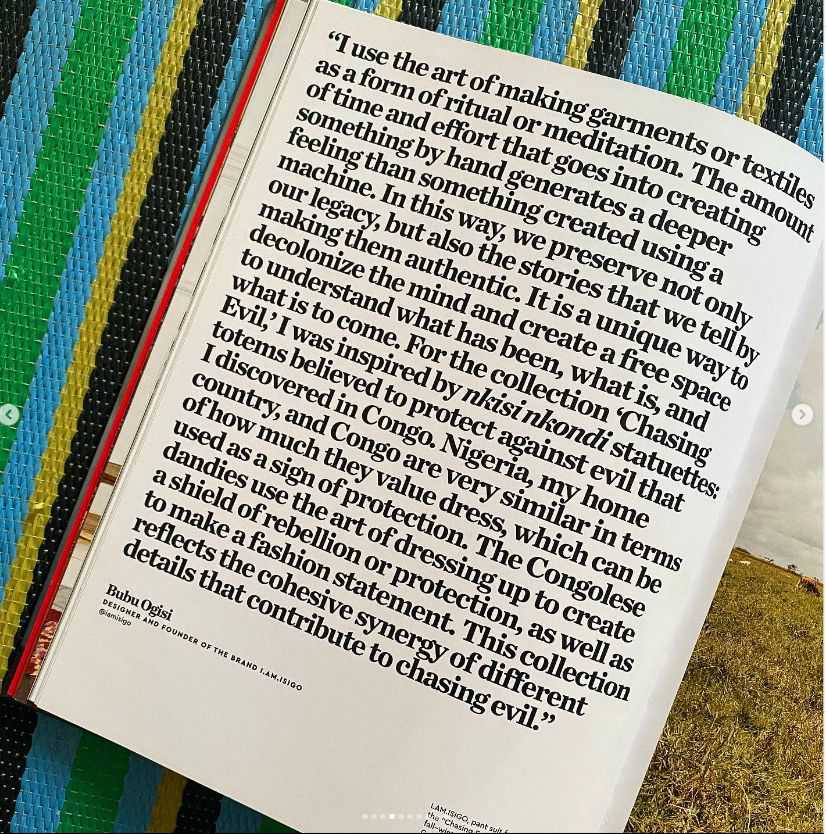

About your collection «Chasing evil», you said (in the book Africa the fashion continent)2 that fashion could be «used as a sign of protection». Can you tell us how?

« Chasing evil » is based on a Congolese statue, nkondi nkissi, a sculpture that has nails nailed throughout the bodice and head and most time with a mirror in the front chest part, used as a protective figurine to chase away evil. I always saw garments as a form of protection. I was working on a project with refugees at that time in Congo, survivors from the war. For me, the whole process of what I was creating for them was to create something so that any person who would see them, would be so afraid to touch them or do any hamr. That’s the whole point of the spirit of the outfit! it is a way to chase the evil as it says: “you can’t do anything to me right now, because I look AMAZING” (laugh).

The work of Bubu Ogisi is part of the exhibition Singulier Plurielles, International Biennale Design Saint-Etienne 2022.

I am not myself exhibition is in The Tetley until august 22.

You can also follow her on her Instagram account.

Macula - L’attirance de l’œilExposition d’étudiant·e·s de l’Esadse et de l’UJM à La Belle Époque

Votre navigateur est obsolète, l’affichage des contenus n’est pas garanti.

Veuillez effectuer une mise à jour.